is america a christian nation?

over the last year or so, religion has been at the forefront of american political discourse. whether it was rev. jeremiah wright, mitt romney’s bid to become the first mormon president, sarah palin’s prophetic utterances at her wasilla place of worship or the bridge that barack obama erected between frank religious conversation and the democratic party, religion was a central figure in the story of politics in 2008.

with the inauguration last month, the issue became even more prominent. one couldn’t watch the inaugural events unfold without a very clear sense of the importance and role of religion in american politics. from several prayers at the inaugural events (which were highly publicized and picked apart in the media) to obama’s attendance at a prayer service the morning after, god was on display in washington.

all these things reignited the conversation of whether or not america is a christian nation. so, is it? allow me to offer a few of the arguments at play in this debate and try to provide some helpful and informative responses. (i’ll begin with some of the weaker arguments and work toward some of the more compelling points of reason.)

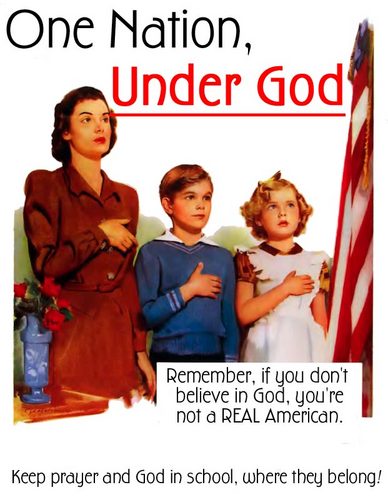

1. our pledge of allegiance says “under god” and our government-printed money says “in god we trust”. doesn’t that say that we are a christian nation?

it’s sad to say, but we christians, unfortunately, love to peddle fear and play the role of martyr. this is no more evident than the flood of emails over the last year or so that say something to the following effect: “christians, stand up and tell the government that we won’t stand for “in god we trust” to be taken off our coins!” well, first of all, they haven’t. that’s a lie. it’s on there. but, let me turn this line of reasoning around.

coins also contain the latin phrase, e pluribus unum, which translates to “in many, one.” e pluribus unum was chosen as the official motto in 1776 by a committee consisting of benjamin franklin, thomas jefferson and john adams. by 1786, the motto was printed on coins. on the other hand, “in god we trust” wasn’t adopted until 1956 (and “under god” was not in the original pledge, as it was inserted in 1954).

the point i’m making is that if we really want to see what this country was founded on, we shouldn’t look at the phrase that was chosen 50 years ago, but rather, we should look at the phrase that was literally chosen by the founding fathers. e pluribus unum suggests a certain plurality to our country. now, it’s not inherently descriptive of religion, but you could argue that that’s a facet of the phrase that’s important to our country’s origins, as we are, indeed, a melting pot in a variety of respects.

2. the founding fathers and pilgrims were christians and since they’re the ones who were here first, aren’t we a christian nation?

a very robust debate could occur as to whether or not all the founding fathers were christians in the “orthodox” sense of the word (i.e. thomas jefferson, most notably), but i have very little interest in picking apart a bunch of old dudes’ worship preferences. instead, i’m much more interested in addressing the argument tactic that says, “whoever’s first sets the standard for the future.” i’m not sure those who employ that tactic are truly prepared to go down that road.

it seems fairly clear to those who are interested in the history of this piece of land that white christians have very little claim to being called “the first.” if we’re going to let the “first” people’s religious preferences set the standard for our country, then we need to begin the practice of polytheistic native american religious expressions. rocks, birds, water, the sun—all these things are to be worshipped and revered as sacred. so, before we start using the “we were here first” argument, let’s take a long look at our history.

3. doesn’t the constitution say that we’re a christian nation and doesn’t it even say something about a “creator”?

no and no. first, the declaration of independence certainly does say the following: “they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights”. it absolutely does. two problems. first, the declaration of independence doesn’t govern our country. second, and most important, what about the word “creator” implies christian? doesn’t islam believe in a creator? doesn’t judaism believe in a creator? every “major” religion in the world believes in some sort of “creator.” i think thomas jefferson was keenly aware of his ambiguous language. the founding fathers—who were christians, of course—could have easily put very explicitly christian language, but chose not to do so.

it’s important to understand that the constitution has no explicit christian language, either. there are two religious references in the constitution. first, it says that the government will not establish a religion or impede the free exercise thereof (my paraphrase). in other words, unlike england at the time, our government will not support a state church or religion. further, the government won’t tell anyone they can’t worship freely in their church of choice. explicitly, the constitution paves the way for a plurality of religions, as it will not stop anyone from worship god, allah, buddha or no god at all. the second reference forbids the use of a required religious test as a requirement for an elected office. in other words, you can be christian, buddhist, mormon or atheist and that (in theory) should no affect your chance of becoming the president of a mayor or a county coroner. the constitution is very clear in not just distancing itself from establishing a christian nation, but in assuring a religious plurality.

4. the vast majority of people are christians in america, so doesn’t that make this a christian nation?

my final and most important argument shifts from empirical arguments to my own sense of reason and theological sensibilities. i propose the following counter question: “how, do you suppose, that a country—an intangible claim of land ownership and self-imposed boundaries—have a redemptive and salvific realtionship with jesus the messiah?” in other words, i call myself a christian because i have come into relationship with jesus christ. i have chosen to follow christ, through repentance and my rational decision to commit to a lifestyle of sacrifice and love and grace. i find it difficult to see how a country—an abstract claim by a governing body and people—can come into relationship with jesus and live life in the aforementioned manner.

for years, i’ve used this argument in other facets of life and culture. christian music? what is that? how is it that notes and melodies and rhythms are any more christian than another set of notes and melodies and rhythms? certainly, lyrics can speak of christ and the christian experience, but there’s nothing inherently sanctified or holy about words and phrases. if i go to a non-english speaking community and start singing “amazing grace”, they’re more likely to look at me like i’m crazy than drop to their knees and commit to following jesus. words are only meaningful to the culture that ascribes their meaning. christian movies? same thing. christian books? nope. just by slapping the word “christian” in front of a word doesn’t make it holy or sacred of “of christ.” not music. not a movie. and certainly not a nation.

there are certainly many more reasons and examples that could further support my claim that america, indeed, is not a christian nation. i’m a christian. and my wife’s a christian. and many of my neighbors are christians. and many people in this state are christians. and many, many people in this country are christians. and many of our founding fathers were christians. and there are certainly many christian words and symbols prominently displayed and used in our country (even our government). but these things don’t inherently make america a christian nation.

don’t get me wrong, my proverbial dog in this fight is christianity, but part of the beauty of america is the freedom to be anything. for instance, a christian. or a buddhist. or a muslim. or an atheist. that’s not troubling. it’s beautiful. it gives us an opportunity to bridge gaps and understand life and faith through various lenses. when faith is empiricized, it becomes inward and stale and cultural (just ask constantine…or many people in the bible belt…). throughout history, we see that when christianity has been disenfranchised, it has flourished. (which is a whole other blog post…and trust me, i’m not advocating that christianity be disenfranchised in america…i’m just making the point.)

so, before i get too far off track (and get myself in trouble…), let me wrap this up by unequivocally saying that nothing about our nation is inherently “christian.”