good copy bad copy and the great confession, pt.2

just in case you didn’t read my last post, you probably want to back up and give it a quick once-over. this is part 2, so it will assume that you’ve read the previous post.

in my unfolding discovery of girl talk’s feed the animals (along with the jaydiohead album), i came across a 2007 documentary called good copy bad copy. the film takes a look at the very issues that i prefaced in part 1 of this post: copyright laws, illegal file sharing, sampling and, generally speaking, the “free” culture that has represented the growing majority of music consumption over the last 10 years. (by the way, in the spirit of the movie, you can watch the entire thing on their website or you can download the torrent. worth your watch.)

while there were certainly things about the documentary that could have been better (editing, for example), overall, it was a really good and interesting look at the culture i’ve described from several angles. now, let me pause and say that, much like many documentaries, there is a distinct angle, in my opinion. it seemed clear that the filmmakers are coming at this from the point of view that “illegal” file sharing is a viable and acceptable model of music consumption and that copyright laws largely serve to curb creativity and the availability of cultural beauty and enrichment.

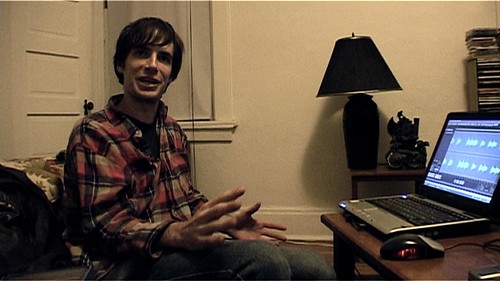

the film opens with the aforementioned gregg gillis (girl talk), in his sparse and diminutive apartment living room, putting together samples on his tiny little laptop. two things instantly strike you as somewhat hilarious. first, this guy is just a music tech nerd who has a lot of time on his hands. of course, it helps to know that gillis, a resident of pittsburgh, was a biomedical engineer before quitting his job to focus on his music full time less than 2 years ago. basically, he’s just a flannel-wearing dude who knows how to use pro tools (or acid pro…or whatever he uses) and enjoys the art of sampling (of which you can tell he is enthralled and passionate).

the second thing that is just crazy is that it’s just him sitting there (the image to the left is a still from the movie) with this tiny little crappy looking pc laptop. i mean, at least give me a mac running garageband. 🙂 it just seems so bizarre that this guy who is putting out this incredible music is putting it together by copying and pasting snippets of music on this little laptop with crappy little speakers. of course, this would have been shot a few years ago, so i’m sure he’s moved up in the world, but it just strikes you as bizarre.

he begins the film by setting the stage as an advocate for artists like himself to have the freedom to use copyrighted music in whatever way they see fit. his argument is primarily based on the idea that art like he and others (like danger mouse of the producer of jaydiohead) wouldn’t be able to produce this art form with the current copyright structures because the licensing of all 322 songs would cost literally millions of dollars. even for the most successful artists in the industry, that kind of licensing expenditure isn’t possible. further, he makes a broad argument for the idea of fair use. he only samples segments of the music, so he claims (like other rap pioneers, as portrayed in the film) that he should be able to use them in limited forms without licensing fees.

as the film moves on, we see other artists and advocates for gillis’ assertion, as well as those who are directly opposed to their point-of-view. one of the chief voices of dissent is the ceo of the mpaa, dan glickman. he argues from a constitutional point-of-view and, generally, along the lines of protecting the content creators. he argues, like others, that if artists and content creators can’t rest assured that they will be protected, it will stifle creativity and, in effect, kill the very content that people are stealing.

to me, the greatest voice of reason in the film was lawrence lessig, a law professor at stanford and one of the founders of the creative commons licensing structure (which is basically a licensing model that isn’t free, but allows artists to employ licensing that tells consumers that it’s ok to use their work in a non-commercial way at their own discretion). lessig’s primary argument isn’t completely focused on advocating a free-for-all music culture, but he certainly advocates the music industry waking up and realizing that the current copyright laws and licensing models do nothing but stifle creativity and the impede the flow of cultural forms of art and enrichment. most compelling, though, is lessig’s very brief history lesson in “content sharing.”

he suggests that long ago, in the fledgling phases of printing presses and the book industry, a fervor arose over people sharing and reprinting books. from this cultural and technological debate came the library system. (when he brought up this argument, i laughed because i fairly recently blogged about a quote from doug pagitt where he said that “the library is the napster of book selling.” hilarious.) anyway, in essence, lessig suggests that if we were to rewind time to the dawn of public libraries, many people would have, as paggitt suggested, viewed the library system as undermining people who make a living from writing, printing and selling books. when a library singularly buys a book and then starts dishing it out to people for free, you stifle the creative industry of writing and book-making. now, far removed from a society without libraries, that idea seems absurd to us, but it wouldn’t have been so absurd at that time—especially if you were an author who needed to pay his or her bills with the revenue from book sales.

what we certainly know and believe, though, is that a society that fosters and makes available forms of art and content that stimulate people’s minds and fosters creativity and an inquisitive spirit, we are a much better society. the government spends millions of dollars every year in funding libraries and making people aware of all the free books that are available at their local library.

has sharing books stifled the will and creativity of content creators? absolutely not. there were more books released last year than any other year before. and so was the same in 2007 and 2006 and 2005. there are more authors than ever who released more books than ever. no doubt the print industry, in general, has suffered a little in the last few years, but it isn’t because of a lack of content creators.

what’s different about an author who writes a book and a musician who creates a song? very little, lessig (and i) would respond. so, the point he is making is that, like the publishing industry, the music industry needs to embrace a new model of distribution and consumption that takes into account the consumer and the technological advances that are never-ceasing.

ok, enough with the analysis of the film and onto the part of the post title that promises my “great confession.” i think we all know where i’m headed here, so this climactic moment will be a little anti-climactic.

i download music.

a lot.

oh, i don’t mean from itunes or amazon or whatever.

i mean torrents (bit torrent, etc.). torrent being the key word. as in torrential.

now, let me pause and say, for whatever it’s worth, that i do actually buy quite a bit of music. i’m not a “only download it for free” kind of person. in fact, i’ve tried to actually cut down on how much music i buy just because we don’t have a lot of discretionary income.

over the years, i’ve thought a lot about the ramifications of my decision and i’ve had mixed feelings. now, though, i have fairly solid feelings about it. i’ve come to the point, for several reasons, that i have no qualms about downloading music. let me list a couple of them.

1. for me, downloading music is a discovery tool and a gateway to becoming a fan. being a person that is constantly on the search for new music, it inherently means consuming a lot of music (be it on blogs or social networks or where ever). i listen to a lot of music. generally speaking, if i hear a song on a blog and it seems ok, i go straight to the artist’s myspace page (or comparable site) to hear a little more. if the music further strikes me as something i may like, i will then download their album. it’s a discovery process.

what then happens is one of two things. either i am thankful i didn’t waste my money on buying an album i didn’t like, OR, i am then converted into a fan. the very thing that makes me such an adamant fan of music and a lifelong music consumer is the ability to download music. let me offer a few examples of the impact of downloading and fan conversion by listing a handful of my favorite artists of all time.

ray lamontagne: knowing very little about him, i downloaded his first album, trouble. since that time, i have purchased 4 of his albums, including, in retrospect, trouble.

jenny lewis: after hearing some buzz about a band called rilo kiley, i downloaded their album, more adventurous. since that time, not only have i bought their next album, under the blacklight, but their lead singer, jenny lewis, is one of my favorite artists and have bought both her solo albums.

damien rice: much like lamontagne, i heard a little buzz about this new artists and decided to download his first album, o. since that time, i’ve become mega-fan and bought 3 of his albums (again, like lamontagne) including o.

brandi carlile: i downloaded her album, the story, knowing virtually nothing about her music (except a clip i heard on a blog). i now eagerly await the follow-up album, which i will buy the morning it comes out.

sheryl crow: here’s a little bit of a different scenario, but illustrates another facet to this argument. long before that napster dude ever dreamed about electronic file sharing, sheryl crow was an artist that i had absolutely no interest in. my older brother, though, really liked her. somewhere along the way, i decided to give her another try and burned a copy of her album, tuesday night music club. after hearing more than just the singles, i fell in love and now sheryl crow is an artist who i eagerly anticipate her album releases and typically pre-order them upon their announcement.

these are just a very few examples. i could easily name probably 25 or 30 more artists who “converted” me into being a paying fan through the ability to “obtain” their music from “friends” online.

2. the second primary reason has less to do with me specifically and more to do with the greater society and the culture therein. i won’t spend a lot of time explaining it because it’s basically the same argument that lawrence lessig laid out in the documentary.

again, it’s not the idea that it should just be a free-for-all, but it’s that the availability and accessibility of cultural forms of art and thought is necessary for current and future creative innovation and civil progression. now, certainly, “current and future creative innovation and civil progression” isn’t completely dependent upon being able to download britney spears albums on bit torrent, but it does certainly mean that when we have a model that encourages creative discovery, we “even the playing field” of creativity and innovative progression. when a cd that cost a couple bucks to produce is being sold for $17, it becomes an exclusive art form. one of the main things that the music industry has done to create this free culture is too effectively say that music is only for people with readily available discretionary income. it becomes a class-dependent commodity—not a form of art that enriches everyone.

now, let me, as i wrap this up (finally) say that there are certainly glaring holes in my reasoning and could be easily argued against. with that said, though, i feel strongly about these issues and have spent a lot of time thinking about them.

so, we’ll see where this whole music industry debate goes. my prediction is that in 5 to 10 years, we’ll look back at this debate and laugh because music distribution and consumption will look much more like what good copy bad copy and artists like girl talk advocates. i guess we’ll see.